Speech Presented to Eris Society

Introduction: The Intrusion of Eris

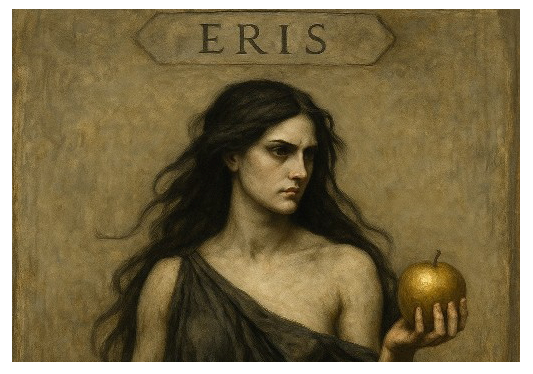

Chaos has a bad name in some parts. It was chaos that brought us the Trojan War (Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, chapter 159). Eris, goddess of chaos, upset at not being invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, showed up anyway and rolled a golden apple marked “kalliste” (“for the prettiest one”) among the guests. Each of the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite claimed the golden apple as her own. Zeus, no fool, appointed Paris, son of Priam, king of Troy, judge of the beauty contest. Hermes brought the goddesses to the mountain Ida, where Paris first tried to divide the apple among the goddesses, then made them swear they wouldn’t hold the decision against them. Hermes asked Paris if he needed the goddesses to undress to make his judgment, and he replied, Of course. Athena insisted Aphrodite remove her magic girdle, the sexy underwear that made everyone fall in love with her, and Aphrodite retorted Athena would have to remove her battle helmet, since she would look hideous without it.

As Paris examined the goddesses individually, Hera promised to make Paris the lord of Asia and the richest man alive, if she got the apple. Paris said he couldn’t be bribed. Athena promised to make Paris victorious in all his battles, and the wisest man alive. Paris said there was peace in these parts. Aphrodite stood so close to Paris he blushed, and not only urged him not to miss a detail of her lovely body, but said also that he was the handsomest man she had seen lately, and he deserved a woman as beautiful as she was. Had he heard about Helen, the wife of the king of Sparta? The goddess promised Paris she would make Helen fall in love with him. Naturally Paris gave the apple to Aphrodite, and Hera and Athena went off fuming to plot the destruction of Troy. That is, Aphrodite got the apple, and Paris got screwed.

While the Greeks had a specific goddess dedicated to Chaos, early religions gave chaos an even more fundamental role. In the Babylonian New Year festival, Marduk separated Tiamat, the dragon of chaos, from the forces of law and order. This primal division is seen in all early religions. Yearly homage was paid to the threat of chaos’s return. Traditional New Year festivals returned symbolically to primordial chaos through a deliberate disruption of civilized life. One shut down the temples, extinguished fires, had orgies and otherwise broke social norms. The dead mingled with the living; Afterward you purified yourself, reenacted the creation myth whereby the dragon of chaos was overthrown, and went back to normal. Everyone had fun, but afterward order was restored, and the implication was it was a good thing we had civilization, because otherwise people would always be putting out the fires and having orgies.

Around us in the world today we see the age-old battle between order and chaos. In the international sphere, the old order of communism has collapsed. In its place is a chaotic matrix of competing, breakaway states, wanting not only political freedom and at least a semi-market economy, but also their own money supplies and nuclear weapons, and in some cases a society with a single race, religion, or culture. Is this alarming or reassuring? We also have proclamations of a New World Order, on one hand, accompanied by the outbreak of sporadic wars and US bombing raids in Africa, Europe, and Asia, on the other.

In the domestic sphere we have grass roots political movements, such as the populist followers of H. Ross Perot challenging the old order imposed by the single-party Democratic- Republican monolith. We have a President who is making a mockery out of the office, and a Vice President who tells us we should not listen to any dissenting opinions with respect to global warming. Is this reassuring or alarming?

In the corporate-statist world of Japan we see the current demolition of the mythic pillars of Japanese society: the myth of high-growth, the myth of endless trust between the US and Japan, the myth of full employment, the myth that land and stock prices will always rise, and the myth that the Liberal Democratic Party will always remain in power. Is the shattering of these myths reassuring or alarming?

In fact, wherever we look, central command is losing control. Even in the sphere of the human mind we have increasing attention paid to cases of multiple personality. The most recent theories see human identity and the human ego as a network of cooperative subsystems, rather than a single entity. (Examples of viewpoint are found in Robert Ornstein, Multimind, and Michael Gazzanaga, The Social Brain.) If, as Carl Jung claimed, “our true religion is a monotheism of consciousness, a possession by it, coupled with a fanatical denial of the existence of fragmentary autonomous systems,” then it can be said that psychological polytheism is on the rise. Or, as some would say, mental chaos. Is this reassuring or alarming?

Myth of Causality Denies Role of Eris

The average person, educated or not, is not comfortable with chaos. Faced with chaos, people begin talking about the fall of Rome, the end of time. Faced with chaos people begin to deny its existence, and present the alternative explanation that what appears as chaos is a hidden agenda of historical or prophetic forces that lie behind the apparent disorder. They begin talking about the “laws of history” or proclaiming that “God has a hidden plan”. The creation, Genesis, was preceded by chaos (tohu-va- bohu), and the New World Order (the millennium), it is claimed, will be preceded by pre-ordained apocalyptic chaos. In this view of things, chaos is just part of a master agenda. Well, is it really the case there is a hidden plan, or does the goddess Eris have a non- hidden non-plan? Will there be a Thousand Year Reign of the Messiah, or the Thousand Year Reich of Adolph Hitler, or are these one and the same?

People are so uncomfortable with chaos, in fact, that Newtonian science as interpreted by Laplace and others saw the underlying reality of the world as deterministic. If you knew the initial conditions you could predict the future far in advance. With a steady hand and the right cue tip, you could run the table in pool. Then came quantum mechanics, with uncertainty and indeterminism, which even Einstein refused to accept, saying “God doesn’t play dice.” Philosophically, Einstein couldn’t believe in a universe with a sense of whimsy. He was afraid of the threatened return of chaos, preferring to believe for every effect there was a cause. A consequence of this was the notion that if you could control the cause, you could control the effect.

The modern proponents of law and order don’t stop with the assertion that for every effect, there is a cause. And they also assert they “know” the cause. We see this attitude reflected by social problem solvers, who proclaimed: “The cause of famine in Ethiopia is lack of food in Ethiopia.” So we had rock crusades to feed the starving Ethiopians and ignored the role of the Ethiopian government. Other asserted: “The case of drug abuse is the presence of drugs,” so they enacted a war on certain drugs which drove up their price, drove up the profit margins available to those who dealt in prohibited drugs, and created a criminal subclass who benefited from the prohibition. Psychologists assert: “The reason this person is this way is because such-and-such happened in childhood, with parents, or siblings, or whatever.” So any evidence of abuse, trauma, or childhood molestation–which over time should assume a trivial role in one’s life–are given infinite power by the financial needs of the psychotherapy business.

You may respond: “Well, but these were just misidentified causes; there really is a cause.” Maybe so, and maybe not. Whatever story you tell yourself, you can’t escape the fact that to you personally “the future is a blinding mirage” (Stephen Vizinczey, The Rules of Chaos). You can’t see the future precisely because you don’t really know what’s causing it. The myth of causality denies the role of Eris. Science eventually had to acknowledge the demon of serendipity, but not everyone is happy with that fact. The political world, in the cause-and-effect marketing and sales profession, has a vested interest in denying its existence.

Approaches to Chaos

In philosophy or religion there are three principal schools of thought (in a classification I’ll use here). Each school is distinguished by its basic philosophical outlook on life. The First School sees the universe as indifferent to humanity’s joys or sufferings, and accepts chaos as a principle of restoring balance. The Second School sees humanity as burdened down with suffering, guilt, desire, and sin, and equates chaos with punishment or broken law. The Third School considers chaos an integral part of creativity, freedom, and growth.

I. First School Approach: Attempts to Impose Order Lead to Greater Disorder

Too much law and order brings its opposite. Attempts to create World Government will lead to total anarchy. What are some possible examples?

- The Branch Davidians at Waco. David Koresh’s principal problem was, according to one FBI spokesman, that he was “thumbing his nose at the law”. So, to preserve order, the forces of law and order brought chaos and destruction, and destroyed everything and everyone. To prevent the misuse of firearms by cult members, firearms were marshaled to randomly kill them. To prevent alleged child abuse, the forces of law and order burned the children to death.

- Handing out free food in “refugee” camps in Somalia leads to greater number of starving refugees, because the existence of free food attracts a greater number of nomads to the camps, who then become dependent on free food, and starve when they are not fed.

- States in the US. are concerned about wealth distribution. But, to finance themselves, more and more states have turned to the lottery. These states thereby create inequality of wealth distribution by giving away to a few, vast sums of cash extracted from the many.

The precepts of the first school find expression in a number of Oriental philosophies. In the view of this school, what happens in the universe is a fact, and does not merit the labels of “good” or “bad”, or human reactions of sympathy or hatred. Effort to control or alter the course of macro events (as opposed to events in ones personal life) is wasted. One should cultivate detachment and contemplation, and learn elasticity, learn to go with the universal flow of events. This flow tends toward a balance. This view finds expression in the Tao Teh King:

The more prohibitions you have,

the less virtuous people will be

The more weapons you have,

the less secure people will be.

The more subsidies you have,

the less self-reliant people will be.Therefore the Master says:

I let go of the law,

and people become honest.

I let go of economics,

and people become prosperous.

I let go of religion,

and people become serene.

I let go of all desire for the common good,

and the good becomes common as grass.

(Chapter 57, Stephen Mitchell translation.)

You don’t fight chaos any more than you fight evil. “Give evil nothing to oppose, and it will disappear by itself” (Tao Teh King, Chapter 60). Or as Jack Kerouac said in Dr. Sax: “The universe disposes of its own evil.” Again the reason is a principal of balance: You are controlled by what you love and what you hate. But hate is the stronger emotion. Those who fight evil necessarily take on the characteristics of the enemy and become evil themselves. Organized sin and organized sin-fighting are two sides of the same corporate coin.

II. Second School Approach: Chaos is a Result of Breaking Laws

In the broadest sense, this approach a) asserts society is defective, and then b) tells us the reason it’s bad is because we’ve done wrong by our lawless actions. This is the view often presented by the front page of any major newspaper. It’s a fundamental belief in Western civilization.

In early Judaism and fundamentalist Christianity, evil is everywhere and it must be resisted. There is no joy or pleasure without its hidden bad side. God is usually angry and has to be propitiated by sacrifice and blood. The days of Noah ended in a flood. Sodom and Gomorra got atomized. Now, today, it’s the End Time and the wickedness of the earth will be smitten with the sword of Jesus or some other Messiah whose return is imminent.

In this context, chaos is punishment from heaven. Or chaos is a natural degenerate tendency which must be alertly resisted. In the Old Testament Book of Judges, a work of propaganda for the monarchy, it is stated more than once: “In those days there was no king in Israel: every man did that which was right in his own eyes” (Judg. 17:6; 21:25). Doing what appeals to you was not considered a good idea, because, as Jeremiah reminds us “The heart [of man] is deceitful above all things and desperately wicked” (Jer. 17:9).

And in the New Testament, the rabbinical lawyer Paul says “by the law is the knowledge of sin” (Rom. 3:20), and elsewhere is written, “Whososever committeth sin transgresseth also the law: for sin is the transgression of the law.” (1 John 3:4). And, naturally, “the wages of sin is death” (Rom. 6:23).

New age views of karma are similar. If you are bad, as somehow defined, you built up bad karma (New Age view), or else God later burns you with fire (fundamentalist Christian view). For good deeds, you get good karma or treasures in heaven. It’s basically an accountant’s view of the world. Someone’s keeping a balance sheet of all your actions, and toting up debits or credits. Of course, some religions allow you to wipe the slate clean in one fell swoop, say by baptism, or an act of contrition, which is sort of like declaring bankruptcy and getting relief from all your creditors. But that’s only allowed because there has already been a blood sacrifice in your place. Jesus or Mithra or one of the other Saviors has already paid the price. But even so, old Santa Claus is up there somewhere checking who’s naughty or nice.

What is fundamental about this approach is not the specific solution to sin, or approach to salvation, but the general pessimistic outlook on the ordinary flow of life. The first Noble Truth of Buddha was that “Life is Sorrow”. In the view of Schopenhauer, Life is Evil, and he says “Every great pain, whether physical or spiritual, declares what we deserve; for it could not come to us if we did not deserve it” (The World as Will and Representation). Also in the Second School bin of philosophy can be added Freud, with his Death Wish and the image of the unconscious as a murky swamp of monsters. Psychiatry in some interpretations sees the fearful dragon of chaos, Tiamat, lurking down below the civilized veneer of the human cortex.

The liberal’s preoccupation with social “problems” and the Club of Rome’s obsession with entropy are essentially expressions of the Second School view. Change, the fundamental motion of the universe, is bad. If a business goes broke, it’s never viewed as a source of creativity, freeing up resources and bringing about necessary changes. It’s just more unemployment. The unemployment-inflation tradeoff as seen by Sixties Keynesian macroeconomics is in the Second School spirit. These endemic evils must be propitiated by the watchful Priests of Fiscal Policy and the Federal Reserve, and you can only reduce one by increasing the other. This view refuses to acknowledge that one of the positive roles of the Market is as a job destroyer as well as a job creator.

More generally, the second school has generated whole industries of “problem solvers”— politicians, bureaucrats, demagogues, counselors, and charity workers who have found the way to power, fame, and wealth lies in championing causes and mucking about in other people’s lives. Whatever their motivations, they operate as parasites and vampires who are healthy only when others are sick, whose well-being increases in direct proportion to other people’s misery, and whose method of operation is to give the appearance of working on the problems of others. Of course if the problems they champion were actually solved, they would be out of a job. Hence they are really interested in the process of “solving” problems–not in actual solutions. They create chaos and destruction under the pretense of chaos control and elimination.

III. Third School Approach: Chaos is Necessary for Creativity, Freedom, and Growth

You find this view in a few of the ancient Greek writers, and more recently in Nietzsche. Nietzsche says: “One must still have chaos in one to give birth to a dancing star.” The first fundamental point of view here is: Existence is pure joy. If you don’t see that, your perception is wrong. And we are not talking about Mary Baker Eddy Christian Science denial of the facts. In this approach you are supposed to learn to alchemically transmute sorrow into joy, chaos into art. You exult in the random give and take of the hard knocks of life. It’s a daily feast. Every phenomenon is an Act of Love. Every experience, however serendipitous, is necessary, is a sacrament, is a means of growth.

“Saying Yes to life even in its strangest and hardest problems, the will to life rejoicing over its own inexhaustibility even in the very sacrifice of its highest types–that is what I called Dionysian, that is what I guessed to be the bridge to the psychology of the tragic poet. Not in order to be liberated from terror and pity, not in order to purge oneself of a dangerous affect by its vehement discharge– Aristotle understood it that way [as do the Freudians who think one deals with ones neuroses through one’s art, a point of view which Nietzsche is here explicitly rejecting]–but in order to be oneself the eternal order of becoming, beyond all terror and pity–that joy which included even joy in destroying.” (Twilight of the Idols).

It is an approach centered in the here and now. You cannot foresee the future, so you must look at the present. But because “nothing is certain, nothing is impossible” (Rules of Chaos). You are free and nobody belongs to you. In the opening paragraphs of Tropic of Cancer, Henry Miller says: “It is now the fall of my second year in Paris. I was sent here for a reason I have not yet been able to fathom. I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.”

Your first responsibility is to take care of yourself, so you won’t be a burden to other people. If you don’t do at least that, how can you be so arrogant as to think you can help others? You make progress by adapting to your own nature. In Rabelais’ Gargantua the Abbey of Theleme had the motto: Fay ce que vouldras, or “Do as you will.” Rabelais (unlike the Book of Judges) treats this in a very positive light. The implication is: Don’t go seeking after some ideal far removed from your own needs. Don’t get involved in some crusade to save the human race–because you falsely think that is the noble thing to do–when what you may really want to do, if you are honest with yourself, is to stay home, grow vegetables, and sell them in a roadside market. (Growing vegetables is, after all, real growth–more so than some New Age conceptions.) You have no obligation under the sun other than to discover your real needs, to fulfill them, and to rejoice in doing so.

In this approach you give other people the right to make their own choices, but you also hold them responsible for the consequences. Most social “problems”, after all, are a function of the choices people make, and are therefore insolvable in principle, except by coercion. One is not under any obligation to make up for the effects of other people’s decisions. If, for example, people (poor or rich, educated or not) have children they can’t care for or feed, one has no responsibility to make up for their negligence or to take on one’s own shoulders responsibility for the consequent suffering. You can, if you wish, if you want to become a martyr. If you are looking to become a martyr, the world will gladly oblige, and then calmly carry on as before, the “problems” unaltered.

One may, of course, choose to help the rest of the world to the extent that one is able, assuming one knows how. But it is a choice, not an obligation. Modern political correctness and prostituted religion have tried to turn all of what used to be considered virtues into social obligations. Not that anyone is expected to really practice what they preach; rather it is intended they feel guilty for not doing so, and once the guilt trip is underway, their behavior can be manipulated for political purposes.

What would, after all, be left for social workers to do if all social problems were solved? One would still need challenges, so presumably people would devote themselves to creative and artistic tasks. One would still need chaos. One would still need Eris rolling golden apples.

Conclusion

In the revelation given to Greg Hill and Kerry Thornley, authors of Principia Discordia, or How I Found Goddess and What I Did to Her When I Found Her, the goddess Eris (Roman Discordia) says: “I am chaos. I am the substance from which your artists and scientists build rhythms. I am the spirit with which your children and clowns laugh in happy anarchy. I am chaos. I am alive, and I tell you that you are free.”

Today, in Aspen, Eris says: I am chaos. I am alive, and I tell you that you are free.